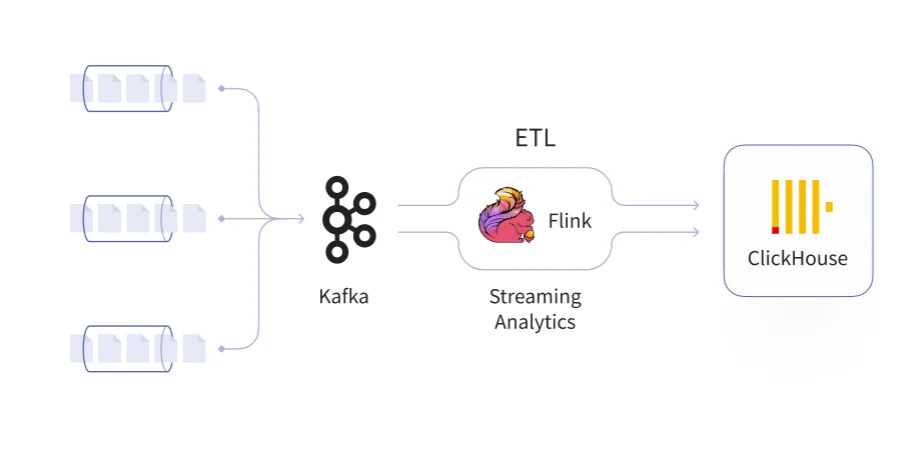

We often see data platforms combining Kafka, Flink, and ClickHouse. Let's discuss when it works, when it's overkill, and where the boundary lies.

Data platform architecture patterns like Lambda and Kappa were proposed to deal with large-scale data processing and bridge the gap between streaming analytics and data-lake queries over historical data. Lambda introduced parallel batch and speed layers - a model that worked but imposed duplicate codepaths and constant reconciliation. Kappa simplified this by treating the (immutable) Kafka events log as the single source of truth and running all processing through a streaming framework. That idea was also the catalyst for creating Flink.

As data volumes grow and data technologies mature in production, architectures have evolved and often outgrew these abstract patterns. Over the past few years, working with organizations across industries, we've seen one particular combination surface repeatedly - both in systems we've designed from scratch and in existing platforms we've been called to optimize. We call it the KFC Architecture Blueprint: Kafka, Flink, and ClickHouse.

Three technologies, each dominant in its domain, that together form an end-to-end solution for real-time data processing and analytics - from ingestion through transformation to sub-second analytical queries. It's less of an abstract architecture and more of a concrete technology blueprint, and when applied to the right use case, it can transform how an organization handles its analytics platform. But it can also be a blackhole of resources for maintenance and debugging.

Why Kafka, Flink, and ClickHouse

Each component in the KFC stack solves a distinct problem, is a technology that has aged well and has proven itself in production at scale, and the three fit together and complement each other well.

Kafka serves as the event streaming backbone. Its log-based, append-only architecture provides durable, ordered event storage with configurable retention. Producers and consumers are fully decoupled and can easily scale out - data sources write events without knowing who reads them, and consumers process at their own pace or rewind to replay history. Kafka's role in the stack: accept events from every source, store them durably, and make them available to any number of downstream consumers.

Flink handles stateful stream processing - the logic that sits between raw event ingestion and analytical storage. It can processes events based on event-time or arrival-time, handles late and out-of-order data, and can maintains distributed state across millions of keys. Its checkpointing mechanism enables recovery to the exact point of failure with no data loss. Combined with Kafka's two-phase commit protocol, Flink delivers end-to-end exactly-once semantics - a hard requirement for financial transactions, billing, and fraud detection. Windowed joins, sessionization, complex event processing, and multi-stream enrichment are where Flink really shines.

ClickHouse is the high-performance analytical store at the end of the pipeline. The rising star of the analytics databases. Its columnar storage and vectorized query execution enable unmatched performance and cost-effectiveness for Data Warehouse and Real-Time Analytics alike. The MergeTree engine family offers variants for different access patterns - ReplacingMergeTree for deduplication, AggregatingMergeTree for pre-aggregation, SummingMergeTree for automatic rollups. ClickHouse routinely handles billions of rows with sub-second query latency, making it suitable for both internal dashboards and user-facing analytics products.

The data flow in a KFC platform is clean and fully optimized: sources produce events into Kafka topics. Flink consumes and transforms them - joining streams, enriching records, computing aggregations, filtering noise, sometimes triggering additional actions - and writes the results to ClickHouse, where analysts and applications query the processed data with sub-second response times.

Where the KFC Blueprint Fits

The KFC pattern is particularly well-suited for large-scale data platforms with strict requirements around data freshness, reliability, and cost - scenarios where high-volume event ingestion, real-time processing, and fast analytics all need to coexist. There are quite a handful scenarios where this is applicable, for example:

Real-time fraud detection is a natural fit. Kafka ingests transaction events from payment systems. Flink applies windowed pattern detection - velocity checks, geo-anomaly scoring, on-the-fly ML model inference - and enriches events with user profiles. Flagged transactions land in ClickHouse, where analysts query billions of rows to investigate fraud rings, tune detection rules, and build dashboards. ClickHouse can also serve the online layer for "real-time memory" and sub-second record linkage.

Clickstream and product analytics software follows a similar shape. Web and mobile events flow through Kafka. Flink sessionizes the raw clickstream, grouping events into user sessions based on inactivity gaps, computes engagement metrics, and resolves user identity across devices. ClickHouse stores the sessionized data and powers analytics dashboards with drill-down by cohort, geography, or feature flag. Think "your weekly listening report" or internal product metrics.

IoT and fleet telemetry benefits from Flink's ability to handle time-series downsampling and anomaly detection at scale. Sensors emit high-frequency data into Kafka, Flink handles reduction and alerting, and ClickHouse stores processed time-series for aggregation queries like average fuel consumption per route or P99 latency across thousands of edge devices. Real-time advertising analytics needs attribution window joins and deduplication across impression, click, and conversion streams. Financial market data needs VWAP calculations, moving averages, and order-book signals computed in real time, with tick-level data stored for backtesting and compliance reporting.

The common thread: Kafka decouples producers from consumers and provides durability. Flink handles the stateful, time-sensitive logic that's too complex for simple consumers - joins, windows, exactly-once semantics. ClickHouse delivers sub-second analytical queries at scale that traditional OLTP databases can't match. The stack fits wherever you need both real-time processing and fast historical analysis over large volumes of event data.

When Not to Use KFC

Quite honestly, many teams over-engineer by defaulting to a Kafka -> Flink -> ClickHouse architecture when simpler options would cover 80% of their needs with signifcantly less effort. Flink undoubtedly adds real operational complexity: checkpoint tuning, state backend management, job upgrades, backpressure handling. That complexity has to be justified.

When simple pipelines are enough

If your workload is fundamentally "land raw or lightly transformed events into ClickHouse and query them," you don't need Flink. ClickHouse's Kafka Table Engine can consume directly from Kafka topics. Combined with materialized views, it handles straightforward transformations at insert time - filtering, column extraction, light aggregation. This is absolutely doable - for example, Mux replaced their entire Flink layer with cascading materialized views and Null Tables, achieving ~500K writes/sec with consumer lag under a minute.

Other options include Kafka Connect with the ClickHouse sink connector, ClickPipes on ClickHouse Cloud for fully managed ingestion, and tools like Vector, Airflow or writing a custom consumer. Cloudflare runs 106 Go consumers that batch-insert into ClickHouse and process 6 million HTTP requests per second - no Flink in the path.

Start with the simple option. Add Flink only when you hit a concrete wall. The F in KFC can sometimes stand for Friction :)

When you genuinely need Flink

The boundary becomes clear once you know what to look for:

- Windowed joins across streams - joining clicks with impressions within a 30-minute attribution window, or enriching orders with the most recent inventory snapshot, and acting upon it in (near) real-time. These require maintaining state across events over time.

- Complex event processing (CEP) - detecting sequences like "three failed logins followed by a password reset from a different IP within 5 minutes."

- Sessionization - grouping raw clickstream into sessions based on inactivity gaps. Inherently stateful and often too complex to express as a materialized view.

- Exactly-once semantics with side effects - triggering alerts, calling external APIs, or writing to multiple sinks atomically as part of the processing.

- Pre-aggregation at massive scale - reducing write volume to ClickHouse by orders of magnitude through stateful rollups with proper windowing and retraction logic. ClickHouse is amazingly effective at high performance writes, but at some scales it's more efficient to do filtering, sampling or rollups on the stream before it hits ClickHouse.

- Multi-sink routing - processing once and writing to ClickHouse, S3, another Kafka topic, and a cache simultaneously with coordinated checkpointing.

If none of these apply, you probably don't need Flink. The honest test: "Do I need to maintain state across events?" and "Do I need to join multiple streams by time?" If yes, bring in Flink. If not, let ClickHouse handle it.

Key Takeaways

The KFC Architecture Blueprint works because each component excels at its job without trying to do everything. Kafka handles ingestion and decoupling. Flink handles stateful stream processing. ClickHouse handles analytical queries. The boundaries are clean, and each technology is battle-tested at scale by organizations like Cloudflare, eBay, Uber, and Lyft.

But the full stack is not always the right call. Many analytics workloads need only Kafka and ClickHouse, with materialized views handling the transformation. The operational cost of running Flink - checkpoint tuning, state management, cluster sizing - needs to be weighed against the actual processing requirements.

Our recommendation: start with Kafka feeding directly into ClickHouse. When you encounter a requirement that ClickHouse's insert-time processing can't handle - stateful joins, complex windowing, exactly-once delivery - that's when you bring in Flink. Not before.