Master scaling vector search in OpenSearch. Learn how to optimize HNSW parameters, leverage quantization (SQ, BQ, PQ), and architect systems for billion-vector datasets

Modern search implementations use vectors for semantic search (and hybrid search), but scaling it effectively remains one of the most challenging problems in search engineering. Many teams successfully deploy vector search for prototypes only to discover that the path from millions to billions of vectors introduces qualitatively different challenges at each order of magnitude. And this is still a greenfield which keeps seeing innovations.

The most common mistakes we see involve applying yesterday's assumptions to today's scale: treating approximate nearest neighbor search as deterministic when it's probabilistic by design, over-sharding in ways that devastate tail latency, and chasing the final 1-2% of recall at costs that dwarf the first 95%. Understanding these pitfalls - and how OpenSearch's specific capabilities can address them - is essential for building vector search systems that perform reliably at scale.

This guide explores the journey from basic vector search concepts through the sophisticated optimization techniques required to operate at truly massive scale.

Understanding Vector Search Fundamentals

At its core, vector search works by representing data as dense numerical arrays called embeddings. These embeddings capture the semantic essence of the underlying content, whether that content is text, images, audio, or any other data type that can be processed through a machine learning model. When a user submits a query, it too gets converted into an embedding, and the search system finds the stored vectors that are mathematically closest to the query vector.

OpenSearch implements vector search through its k-NN (k-nearest neighbors) plugin, which supports multiple search techniques. The most straightforward approach is exact k-NN search, which compares the query vector against every single vector in the index. While this guarantees finding the truly closest neighbors, it becomes computationally prohibitive as datasets grow beyond a few thousand documents.

For practical applications at scale, approximate k-NN (ANN) search trades a small amount of accuracy for dramatic improvements in speed. Rather than exhaustively comparing against every vector, ANN algorithms use clever data structures to quickly narrow down the search space to the most promising candidates. OpenSearch supports several ANN algorithms, but the most widely used is HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World).

The HNSW Algorithm: A Deeper Look

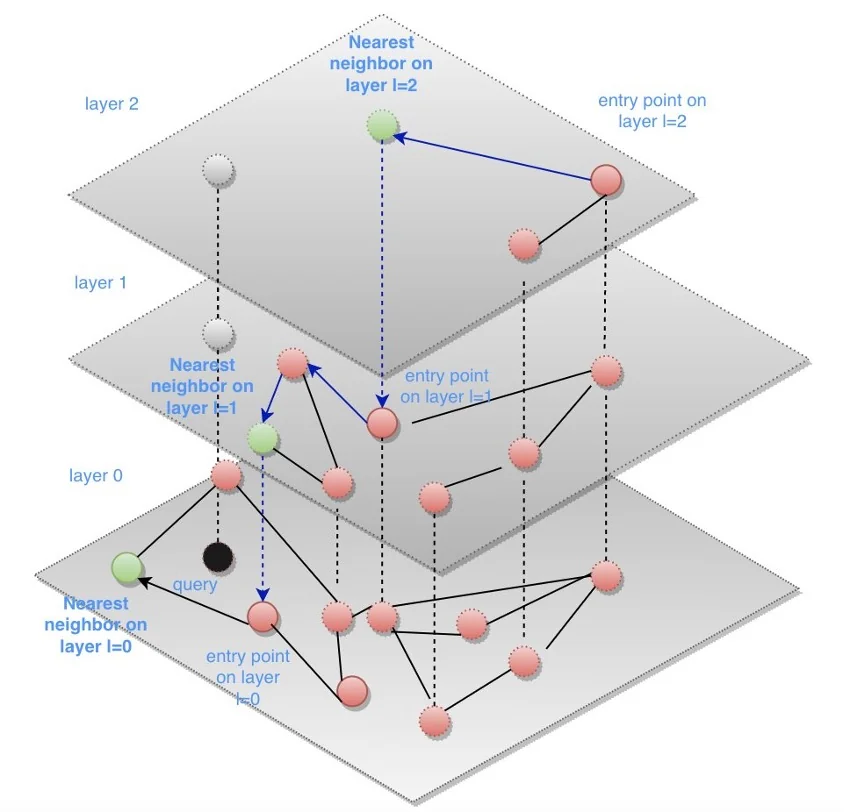

HNSW has become the dominant algorithm for approximate nearest neighbor search due to its excellent balance of search quality, speed, and memory efficiency. Understanding how it works illuminates why certain configuration choices matter so much at scale.

The algorithm constructs a multi-layered graph structure where each layer contains progressively fewer points. The topmost layer is sparse, containing only a handful of well-connected nodes that serve as entry points. Each subsequent layer contains more nodes, with the bottom layer including every vector in the dataset. When searching, the algorithm starts at the top layer and greedily navigates toward vectors that are closer to the query. It then drops down to the next layer, starting from the position it found, and repeats the process. This hierarchical approach allows the search to quickly traverse large distances in the upper layers before fine-tuning the results in the denser lower layers.

The graph structure is built during index creation through an iterative insertion process. Each new vector is connected to its nearest neighbors at each layer where it participates. The quality of these connections directly determines how efficiently the graph can be traversed during search, which is why the index-time parameters have such a significant impact on search performance.

OpenSearch Engine Options

OpenSearch provides three native engines for vector search: Lucene, Faiss, and JVector (nmslib was deprecated in 2.19 and blocked from new index creation in 3.0). Each engine implements HNSW with similar conceptual approaches but with different performance characteristics and feature sets.

The Lucene engine integrates most closely with the broader OpenSearch ecosystem and benefits from ongoing optimizations in the Lucene project. It stores vector data alongside other Lucene index structures, which can simplify operational management. Lucene also provides built-in scalar quantization that can reduce memory requirements while maintaining reasonable recall.

The Faiss engine, developed by Meta, offers additional quantization options including 16-bit scalar quantization and product quantization (PQ). Product quantization is particularly valuable for very large datasets because it can compress vectors significantly more aggressively than scalar quantization, though with a more noticeable impact on recall. Faiss also tends to show strong performance characteristics for larger index sizes.

The JVector engine, introduced as an OpenSearch plugin, addresses one of the key limitations of other engines: single-threaded graph construction. JVector implements concurrent, lock-free vector graph construction that achieves near-linear scalability as you add CPU cores, dramatically accelerating index builds for high-volume ingestion scenarios. Unlike Lucene, JVector is thread-safe and supports concurrent modification and inserts without expensive merge operations. It can also perform index construction with quantized vectors (reducing memory usage and enabling larger segments), refine quantization codebooks during merge for improved recall, and perform incremental vector inserts into previously persisted indexes without full rebuilds. Additionally, JVector supports DiskANN-style search without loading the entire index into RAM, providing flexibility for memory-constrained deployments.

Optimizing HNSW Hyperparameters

Three primary hyperparameters control the behavior of HNSW indexes, and tuning them correctly is essential for achieving optimal performance. These parameters represent fundamental tradeoffs between index build time, memory consumption, search latency, and search accuracy.

The M parameter defines the maximum number of edges (connections) each node maintains in the graph. Higher values create a more densely connected graph that can be traversed more efficiently during search, leading to better recall. However, denser connections also increase memory consumption proportionally and slow down index construction. Typical values range from 16 for memory-constrained environments to 128 for applications requiring maximum recall.

The ef_construction parameter controls the size of the dynamic candidate list maintained during index building. When a new vector is inserted, the algorithm searches for its nearest neighbors using this parameter to guide exploration. Larger values produce higher-quality graphs because the algorithm explores more thoroughly before deciding which connections to create. However, this comes at the cost of significantly longer indexing times. Values typically range from 128 for balanced workloads to 256 or higher for applications prioritizing search quality.

The ef_search parameter operates at query time rather than index time. It determines how many candidates the algorithm tracks while traversing the graph during search. Higher values improve the probability of finding the true nearest neighbors but add latency to each query. This parameter can be adjusted dynamically based on application requirements, making it valuable for balancing recall against response time in production systems.

You should be starting with moderate configurations and progressively increasing parameter values until recall targets are met. A practical approach involves testing configurations in sequence: begin with M=16 and ef_construction=128, measure recall, then try M=32, and continue escalating until requirements are satisfied. For ef_search, values between 32 and 128 cover most use cases, with higher values reserved for applications where maximum recall justifies additional latency.

Beyond basic hyperparameter tuning, several techniques can dramatically improve vector search performance in production environments.

Concurrent Segment Search (CSS) enables parallel execution across segments within each shard, distributing work across multiple CPU cores simultaneously. OpenSearch benchmarks have demonstrated at least 60% improvements in p90 service time when CSS is enabled, with OpenSearch 3.0 achieving up to 75% reduction in p90 latency and 2.5x faster query performance. This improvement comes at the cost of additional CPU utilization, but for workloads where latency is critical and compute resources are available, the tradeoff is highly favorable.

Enabling CSS is straightforward at the cluster level:

PUT _cluster/settings

{

"persistent": {

"search.concurrent_segment_search.enabled": true

}

}

For best results, force-merge segments before enabling CSS to reduce segment count and maximize the benefits of parallelization. However, CSS is not universally beneficial. In situations where the search space is already small or where compute cores are already fully utilized, the overhead of coordinating parallel execution can outweigh the benefits.

Most importantly, memory management is critical for vector search performance. HNSW graph traversal is dramatically faster when the entire graph resides in memory. When memory pressure forces portions of the graph to disk, query latency can increase from milliseconds to seconds due to disk I/O. The knn.memory.circuit_breaker.limit setting controls what percentage of available memory (after excluding JVM heap) can be allocated to k-NN graphs. Monitor for circuit breaker triggers, which indicate that memory is insufficient for the current index size.

For scenarios where memory costs are prohibitive, disk-based vector search (introduced in OpenSearch 2.17) offers a compelling alternative. By setting the mode parameter to on_disk for your vector field, OpenSearch uses binary quantization to compress vectors and store full-precision vectors on disk while keeping only the compressed index in memory. The default compression level of 32x reduces memory requirements by approximately 97% - a dataset of 100 million 768-dimensional vectors that would require over 300 GB of RAM can fit comfortably in under 10 GB with binary quantization.

Disk-based search works through a two-phase approach: during search, the quantized in-memory index quickly identifies candidate results (more than the requested k), then full-precision vectors are lazily loaded from disk for rescoring to maintain accuracy. This architecture trades latency for cost - if your use case tolerates P90 latency in the 100-200 millisecond range, disk mode can reduce infrastructure costs to roughly one-third compared to memory-optimized deployments. Note that disk mode currently only supports the float data type and does not support radial search.

Scaling to Hundreds of Millions of Vectors

As datasets grow beyond tens of millions of vectors, the engineering challenges shift from simple optimization to fundamental architecture decisions. Memory becomes the primary constraint, and strategies that worked well at smaller scales may no longer be viable.

Sharding strategy becomes critical at this scale. The optimal approach is typically to shard by data rather than by query patterns, aiming for individual shards containing 10 to 30 million vectors each. This size range balances the benefits of parallelism against the overhead of aggregating results across shards. Over-sharding creates excessive coordination overhead that harms tail latency, while under-sharding leaves performance on the table.

When the shard count equals or slightly exceeds the node count, each node can process its local shard in parallel with others, maximizing throughput. Adding replicas provides additional benefits beyond availability: replica shards allow load balancing that smooths out performance variations between nodes, so slower nodes or those experiencing network congestion don't become bottlenecks.

Compression becomes mandatory at this scale. OpenSearch offers several quantization techniques that trade precision for memory efficiency:

Scalar quantization (SQ) reduces vector precision from 32-bit floats to smaller representations. The Lucene engine supports built-in scalar quantization, while the Faiss engine offers SQfp16 which automatically converts 32-bit vectors to 16-bit at ingestion time, cutting memory requirements by approximately 50% with modest recall impact.

Binary quantization (BQ) compresses vectors into binary format using 1, 2, or 4 bits per dimension. With 1-bit quantization, you achieve 32x compression - a 768-dimensional float32 vector shrinks from 3072 bytes to under 100 bytes. BQ requires no separate training step, handling quantization automatically during indexing. Combined with asymmetric distance computation (ADC), where uncompressed queries search compressed indexes, recall can be significantly improved over traditional binary approaches.

Product quantization (PQ) provides the most aggressive compression, up to 64x, by splitting vectors into m subvectors and encoding each with a learned codebook. PQ is available for the Faiss engine with both HNSW and IVF methods. The trade-off is more noticeable recall impact and a required training step for IVF-based indexes. A typical configuration uses

code_size=8with m tuned for the desired balance between memory footprint and recall.

A powerful pattern at this scale is two-phase retrieval: use compressed vectors to quickly identify a larger set of candidates (perhaps 10-20 times the final result count), then rerank those candidates using full-precision vectors or additional scoring signals. This approach captures most of the memory savings from aggressive compression while recovering accuracy through the reranking phase.

Periodic index maintenance becomes important as vector indexes accumulate incremental updates. HNSW graph quality can drift over time as new vectors are inserted without full graph optimization. Building fresh indexes periodically or during low-traffic windows helps maintain consistent search quality.

Scaling to Billions of Vectors

At billion-scale deployments, the challenges become qualitatively different from smaller scales. Memory costs dominate infrastructure budgets, query routing decisions directly impact latency, and even small inefficiencies multiply into major operational concerns.

Hierarchical retrieval becomes unavoidable at this scale. Rather than searching a single massive index, effective systems implement multi-stage retrieval pipelines. An IVF (Inverted File) style approach first identifies which cluster centroids are closest to the query, then searches only within the vectors assigned to those clusters. This dramatically reduces the search space while maintaining reasonable recall for most queries.

Multi-tier index architectures separate frequently accessed "hot" data from less active "cold" data. Hot data lives in memory-optimized indexes with higher-quality HNSW graphs and less aggressive compression. Cold data uses aggressive quantization (often IVF-PQ or IVF-SQ) and may partially reside on disk. Intelligent query routing directs requests to appropriate tiers based on query characteristics or explicit user signals.

Asymmetric Distance Computation (ADC) offers significant performance benefits for quantized indexes by computing distances between uncompressed query vectors and compressed database vectors. This approach improves memory locality and cache utilization compared to decompressing database vectors for comparison.

Network optimization matters increasingly at scale. Fan-out queries that touch every shard generate substantial network traffic, especially when returning vector payloads. Returning only IDs and scores from initial retrieval phases, then fetching full documents only for final results, dramatically reduces network bandwidth requirements.

Storage optimization can provide additional benefits. Disabling _source storage and doc_values when they're not needed for the vector search use case can reduce index size substantially, speed up indexing and index maintenance toil, and also assist with search performance.

Query Performance at Scale

Even with optimized indexes, achieving strict latency requirements at high throughput requires careful attention to query-side configuration.

Shard-node relationships strongly influence performance. When shard count is smaller than node count, adding shards increases parallelism and typically reduces latency. When shard count exceeds node count, the benefits plateau and coordination overhead begins to dominate. Many deployments find optimal performance when shard count equals node count, with additional capacity provided through replicas rather than more shards.

The K parameter (how many nearest neighbors to retrieve) affects latency only modestly for reasonable values. Increasing K from 10 to 100 might add only 10-20% to query latency, making it feasible to retrieve larger candidate sets for downstream reranking without severe performance penalties.

CSS applicability varies based on workload characteristics. For some use cases, CSS increased CPU utilization substantially but reduced saturated QPS capacity from 10,000 to 7,000 queries per second due to earlier resource exhaustion. The P99 latency improvement at moderate load was minimal because the search space per shard was already small. CSS provides the most benefit when the search space per shard is large (bigger shards or less restrictive filters), when compute cores are underutilized without it, and when there are multiple segments per shard to parallelize across.

Practical Recommendations by Scale

The following recommendations synthesize the strategies discussed throughout this guide. For a broader perspective on scaling challenges that apply across vector search technologies, see our companion article on scaling vector search from millions to billions.

For millions of vectors (1-50M): HNSW is the right default algorithm. Ensure vectors fit entirely in RAM. Start with M=32, ef_construction=128, and tune ef_search for your recall requirements. Normalize vectors once during ingestion rather than at query time. Use batch inserts to maintain graph quality.

For hundreds of millions (50-500M): Implement systematic sharding with 10-30M vectors per shard. Enable scalar quantization. Consider two-phase retrieval with compressed vectors for initial search and full precision for reranking. Use memory-mapping for cold segments. Monitor recall drift and rebuild indexes periodically.

For billions (500M+): Implement hierarchical retrieval with IVF-style centroid routing. Deploy multi-tier architectures with hot and cold data paths. Use aggressive quantization (IVF-PQ) for cold data. Optimize query routing to avoid blind broadcast to all shards. Return only IDs and scores from initial retrieval phases.

Across all scales, remember that the final 1-2% of recall improvement typically costs disproportionately more than the first 95%. Define realistic recall targets based on application requirements rather than pursuing perfection. Monitor end-to-end latency including embedding generation, metadata retrieval, and any reranking stages, not just the vector search component in isolation.

Conclusion

Scaling vector search from prototype to production and eventually to billions of vectors requires evolving strategies at each stage. The fundamentals of HNSW remain constant: the M parameter controls graph connectivity, ef_construction controls build quality, and ef_search controls query thoroughness. But the optimal values, the surrounding architecture, and the operational practices that work at each scale differ substantially.

Success at scale comes from understanding these tradeoffs deeply: knowing when to invest in graph quality versus when to rely on quantization and reranking, when parallel execution helps versus when it adds overhead, and when to shard more aggressively versus when to scale vertically. OpenSearch provides the building blocks for vector search at any scale, but assembling them effectively requires treating scale not as a single problem but as a continuum of evolving challenges.